Animals have evolved amazing nose adaptations. An elephant’s trunk can pick up objects big and small. The star-nosed mole’s nose acts like a hand for feeling its way underground. These special noses help animals survive. But many big-nosed animals are now in danger. Join us on a safari to learn about these unique creatures and why we must protect them.

Key Takeaways:

- Elephants’ trunks are Swiss army knife-like, with over 40,000 muscles enabling remarkable strength, dexterity, smell, and survival tasks like drinking and interacting with others.

- The star-nosed mole’s star nose acts like an extra limb, transmitting sensory information to its brain with lightning speed to expertly hunt subterranean prey.

- The aardvark’s long snout houses an acute sense of smell that guides its nocturnal insect-feeding forays – up to 50,000 ants per night.

- The tapir’s flexible, extendable snout helps it grab leaves, fruit and shoots while dispersing seeds critical to sustaining biodiverse rainforests.

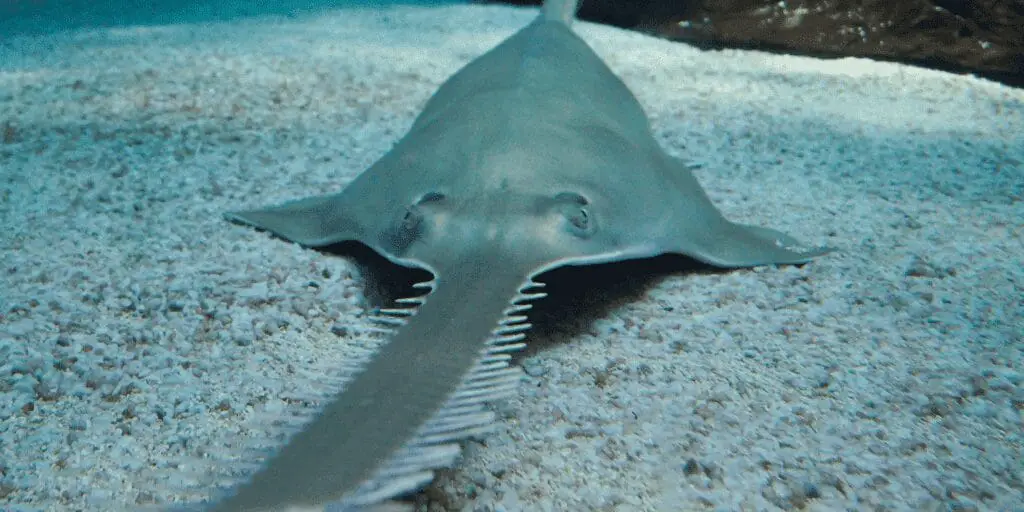

- Overextraction has endangered sawfish whose snouts function magnificently in prey detection but dangerously render them vulnerable to capture.

List of Animals With Big Noses

Elephants, proboscis monkeys, star-nosed moles, aardvarks, tapirs, sawfish, elephant seals, mandrills, long-nosed bandicoots, and snub-nosed monkeys are 10 animals adapted with large, specialized noses enabling unique lifestyles, though many now face conservation threats.

| Animal | Nose Adaptation | Primary Use | Conservation Status |

| Elephant | Trunk with 40,000 muscles | Picking objects, smelling, social interaction | Threatened by poaching and habitat loss |

| Proboscis Monkey | Large, drooping nose | Amplifying calls, social hierarchy | Endangered due to habitat loss and hunting |

| Star-Nosed Mole | 22 fleshy appendages | Sensory organ for underground navigation | Insight into early mammalian sensory evolution |

| Aardvark | Pig-like snout | Feeding on ants and termites | Declining in North and West Africa due to habitat loss |

| Tapir | Extendable proboscis | Grabbing leaves, fruit, and tender shoots | Endangered, vulnerable, or threatened due to habitat loss |

| Sawfish | Elongated snout with teeth | Hunting and sensing prey | Critically endangered due to fishing and habitat loss |

| Elephant Seal | Large, inflatable nose | Signaling dominance, conserving moisture while diving | Recovering but threatened by environmental changes |

| Mandrill | Brightly colored nose | Social communication and hierarchy | Vulnerable due to deforestation and hunting |

| Long-Nosed Bandicoot | Elongated snout | Foraging insects, larvae, and fungi | Near threatened due to predation and habitat loss |

| Snub-Nosed Monkey | Shortened muzzle | Adapting to high-altitude conditions | Endangered due to habitat fragmentation and human activities |

1. The Majestic Elephants: Masters of the Multi-Functional Trunk

Anatomy of the Elephant Trunk

The elephant’s trunk is one of nature’s most remarkable creations. This strong, dexterous organ comprises over 40,000 muscles, divided into circumferential and radiating groups that allow it to bend and twist in all directions. The trunk’s tip is lined with finger-like projections and over 100,000 sensory receptors, giving elephants extreme sensitivity and manual dexterity.

Using their trunks, elephants can pick up objects as small as a coin or as large as a tree trunk. This appendage also serves as an olfactory organ, with millions of cell receptors that can detect scents up to 6 miles away. Scientists have found that an African elephant’s trunk may contain over 40,000 separate muscles!

This gives them the strength and flexibility to use their trunks for everything from sniffing out water holes miles away to gently picking fruit off the branches of trees. It’s no wonder this appendage has been described as a Swiss army knife of nature!

Social and Survival Uses

The elephant trunk is indispensable to the pachyderm way of life. As their primary means of defense and manipulating their environment, elephants rely heavily on their trunks for survival tasks like bathing, drinking, feeding, dusting, sound production, and social interaction. When greeting each other, elephants intertwine their trunks and exchange scent signals and periodic secretions. These behaviors strengthen social bonds between herd members.

By placing their trunk tips in each other’s mouths, elephants can assess the reproductive states of potential mates. On the survival side, elephants use their trunks as snorkels while swimming and to access hard-to-reach food and water sources – even drawing quantities of water into their trunks to drink or spray dust over themselves on hot days. Their versatile appendages also clear pathways through dense brush and grasp logs or tree branches to cross rivers and streams.

Conservation Challenges

Sadly, elephants across Africa and Asia face grave threats from ivory poaching and habitat destruction linked to human encroachment. To lose these majestic creatures would be to lose one of nature’s most wondrous evolutionary marvels.

Organizations like the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) run critical on-the-ground initiatives and policy programs like monitoring elephant populations, protecting migration routes and water holes from farmers and herders, and pushing governments to tackle illegal wildlife trafficking.

As human activities pare down wilderness areas, it’s vital that we make space for these highly social, sensitive creatures who mourn their dead, communicate sophisticated messages, and pass down knowledge across generations – all with the help of their fantastically adapted noses.

2. The Unique Proboscis Monkey: A Nose for Communication

Anatomy and Habitat

The proboscis monkey, found only on the island of Borneo, is aptly named for the male’s large, drooping nose, which can exceed 3 inches in length. This unusual feature is thought to play a role in mate attraction and herd social hierarchies, with bigger noses indicating greater dominance.

These reddish-brown primates inhabit lowland forests and coastal mangroves, traveling in noisy bands up to 100 strong along waterways and swamps where they forage primarily for leaves, seeds and unripe fruit. Their partially webbed feet and leathery toes help them navigate the wet, slippery terrain.

Unfortunately, the proboscis monkey ranks as endangered due to hunting and severe habitat loss from fires, logging and land conversion to oil palm plantations over the past 40 years.

The Megaphone Nose

While odd-looking, the male proboscis monkey’s large nose isn’t just for show – it serves an important purpose in amplifying its piercing honks, hoots and trumpeting calls. This helps the monkeys locate troop members and defend territories across long distances in their dense forest environments along inland rivers.

The nose also emits a loud, snorting alarm if threats are detected. Females vocalize too, using unique calls to reinforce bonds with their young. When resting, proboscis monkeys hoot softly to stay in contact with others nearby. Keeping connected is crucial; juveniles separated from their mothers rarely survive, and lone males struggle to find mates.

Conservation Outlook

Currently, proboscis monkeys are classified as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), with only about 3,000 monkeys left in southern Borneo. These habitat specialists rely on lush, undisturbed forests and mangroves for survival, but over half of their land has been converted for human uses over past decades.

To preserve these unique primates, conservation groups urge governments and corporations to set aside protected corridors along waterways, practice sustainable logging, establish fire-prevention programs near forests, and engage local communities to value wildlife tourism over poaching.

With commitment from conservation partners and responsible land stewardship, the proboscis monkey’s magnificent nose can continue creating its symphony of sounds for generations to come.

3. The Star-Nosed Mole: A Sensory Powerhouse

Anatomy and Behavior

The star-nosed mole derives its name from the 22 pink, finger-like appendages ringing its snout – a structure allowing it to literally “touch” its surroundings with remarkable speed and sensitivity. These fleshy tabs, full of blood vessels and touch receptors, act as a highly advanced tactile sensory organ to guide the tiny mole through its underground world.

Using Etruscan shrews as assistants, it excavates vast tunnel systems up to 3 feet deep hunting small invertebrates, aquatic insects, worms, snails and tiny amphibians it detects with lightning fast nose-tabs. Unique rapid chewing motions – up to 5 munches per second – then enable it to gobble up and assess food sources.

The Brain Behind the Nose

The star-nosed mole’s intricate nasal star requires huge areas of brain matter to process the flood of tactile information transmitted by its 25,000 sensory receptors. Together, the star and mole brain offer neuroscientists an exciting model for studying dynamic sensory processing in mammals. Researchers have found the mole’s sensory capabilities rival vision in speed and acuity.

By mapping signals from nose to brain, they’ve identified separate processing pathways that may allow the mole to execute goal-directed movement patterns like sniffing while simultaneously collecting sensory data from other areas of the star. These neural networks could lend insight into how creature brains multitask and evolve to match extreme sensory specializations.

Sensory Significance

The star-nosed mole gives scientists an unprecedented opportunity to examine the relationships between anatomical structures, neural pathways, and sensory capabilities driving animal behavior. Many believe its nose-brain sensory configuration represents a rare snapshot of early mammalian evolution – when rapid touch and smell dominated creature interaction with the environment rather than vision.

Continuing research on how the mole’s intricate nose processes tactile information so swiftly and accurately promises to uncover neural dynamics applicable to understanding sensory systems across species, including humans. From tiny moles to intricate human brains, decoding the secrets behind senses promises advancements in neuroprosthetics aiding the blind or sensory-impaired.

4. The Aardvark: A Nose for Nocturnal Foraging

Habitat and Diet

With its tubular body, arched back and pig-like snout, the aardvark cuts a distinct profile as it snuffles along the grasslands and savannas of sub-Saharan Africa. These solitary creatures emerge at night to feast on ants and termites detected through their highly developed sense of smell. Powerful claws then enable them to rip into cement-hard termite mounds or ant hills in search of their main fare: insects and larvae.

They also forage for wild fruits and roots or raid underground bee nests for grubs and honey using their long, thin tongues. Each aardvark can lap up as many as 50,000 insects per night with this efficient, sticky implement.

Conservation Status

While not currently threatened overall in Africa, regional aardvark populations in North and West Africa have declined up to 30 percent over the past two decades. As their grassland habitats come under increasing pressure from farming, grazing, tree-cutting for firewood and expanding human settlements, these solitary foragers lose out to livestock and other wildlife.

However, in East and Southern Africa more intact savannas still sustain robust populations, where aardvarks play a useful role in plowing and fertilizing soil via their vigorous digging – improving conditions for future plant growth.

Ecological Importance

As prolific insect predators, aardvarks help regulate ant and termite numbers that could otherwise explode and destabilize landscapes if left unchecked. Their strong burrowing activities also benefit other wildlife; aardvark tunnels serve as nesting sites or refuges from predators for creatures like the African wild dog, lion, porcupine – even smaller animals like hares or owls.

Loss of these subterranean architects may therefore have negative cascading effects. More research focused on the aardvark is critical to quantify its ecosystem services more precisely and determine effective conservation plans moving forward. In supporting this cryptic forager of the African nights, we ultimately support the broader health and diversity of local habitats.

5. The Tapir: A Flexible Snout for Feeding

Species and Habitats

With their hefty, barrel-shaped builds and abbreviated elastic snouts, tapirs cut memorable profiles as they plow through lush jungle landscapes across Latin America and Southeast Asian rainforests. Of the four species, the Brazilian and Malayan tapirs occupy the largest ranges while mountain tapirs and the small Baird’s tapir have much more restricted habitats and populations, intensifying their risk of extinction.

All four share similar black and white facial markings and utilize their agile, extendable proboscises to grab leaves, fruit and tender shoots, with a special preference for their namesake tapir “apples”. Their versatile trunk-like noses also aid in drinking, breathing while swimming, smelling, interacting, and marking paths with scents that signify territories.

Ecosystem Roles

As hungry consumers of many plant species, tapirs roam far and wide dispersing intact seeds that sustain biodiverse forests. Studies show they can deposit over 96 forest species through their scat over various terrains. This helps germinate future stands of fruiting trees and flowering vines relied on by other wildlife and even human groups over the long-term.

Losing tapirs is already shifting plant compositions in certain recovering woodlands towards less useful commercial timber species. Their large foraging ranges also create cleared trails used by smaller forest fauna. All of this connects tapirs to the broader web of rainforest life in intricate ways we are still deciphering.

Conservation Status

Expanding agriculture and logging, hunting, and road mortality have extirpated tapirs from around 40% of their historic range. They now rank globally as endangered, vulnerable or threatened, with the mountain tapir population down to 2500 individuals hanging on in the waning Andean woodlands.

Intensified threats require expanded protected area networks for sheltering tapirs and integrated conservation strategies engaging governments, landowners, infrastructure agencies and local communities across jurisdictions to preserve remaining habitat corridors they rely on.

6. The Sawfish: An Aquatic Hunter’s Tool

Hunting Adaptations

Gliding stealthily through brackish waters and estuaries from the Americas to Africa, sawfish are characterized by elongated, flat snouts lined with sharp teeth along the outer edge. Reaching up to 7 feet in smalltooth sawfish, this distinctive rostrum allows them to slash and disable schooling fish in the dim or stirred-up waters where they dwell.

But it serves another critical purpose – the rostrum’s thousands of electro-sensitive pores can detect weak electrical fields from prey, guiding precise swipes in murky conditions. It also acts as a rake, whisking the seafloor to uncover crustaceans and smaller bottom-dwellers that comprise the sawfish diet. This multipurpose appendage makes these primitive rays consummate hunters.

Habitats and Conservation

Historically ranging widely in inshore subtropical and tropical waters, sawfish populations have plunged by over 80 percent since the early 20th century due to fishing mortality, entrapment in nets, habitat degradation and curio trade demand for rostra.

The unique saws that serve them so well in hunting also make them dangerously vulnerable to capture. Of the world’s five species, four are classified as critically endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), with the last 500 or so smalltooth sawfish confined mainly to the southern US and Australia.

Preservation Outlook

Targeted conservation efforts by groups like Save Our Seas Foundation offer some glimmers of hope, with US sightings and public releases of sawfish doubling since 2015 after enacting fishing bans and requiring safe handling rules. Captive breeding has also expanded to bolster populations before attempting reintroduction.

But regulations must be tightened and enforced internationally, while restoring damaged nurseries and protecting mangroves will reclaim critical habitat. Through active recovery plans integrating research, policy change and habitat protections, it is possible to ensure the survival both of this ancient evolutionary marvel and the many other species depending on the same threatened coastal ecosystems.

7. The Elephant Seal: A Nose for Dominance and Respiration

Breeding and Dominance

The sizes of southern elephant seal males, known as bulls, are imposing – reaching over 20 feet and 8,800 pounds. But during breeding contention, size alone doesn’t rule. Instead, it comes down to the nose. More precisely, which bull can inflate its distinctively large, floppy schnoz to the most impressive proportions.

These engorged air sacs signal masculinity and fitness, intimidating rivals and attracting potential mates as males gather and battle on remote beaches. Vocalizing through nostrils stretched to the size of volleyballs, the message is clear: only contenders with the lung capacity to oxygenate immense bodies win thenose inflation contest and the right to mate with scores of waiting females.

Extreme Diving Adaptations

An expansive nose doesn’t just benefit elephant seals on land; when they depart to sea, those same nostrils assist in conserving moisture. These seals are astonishing divers, plunging over a mile deep for up to 2 hours pursuing squid, rays, sharks and bottom-dwelling prey. To aid their aquatic feats, elephant seal blood has particularly high oxygen storage while the heart slows.

Their flexible snouts pinch shut, minimizing moisture losses. Such superlative adaptations equip them for months wholly submerged, traveling vast stretches of ocean between coastal breeding events. Females even give birth on beaches before returning for months more offshore feeding.

Conservation Efforts

Historically hunted for oil, elephant seals have rebounded under legal protections to over 600,000 individuals found mainly on islands off California and Mexico plus the Antarctic. But environmental changes threaten their krill and fish stocks while disturbance from human recreation or research activities can disrupt sensitive breeding cycles.

Groups like the Marine Mammal Center thus advocate cautious behavioral guidelines for seal interactions, emphasizing that even admirable creatures rely critically on preserving suitable habitats. If effectively maintained, those substantial elephant seal noses can continue their essential signaling and provide for prodigious transoceanic migrations.

8. The Mandrill: Colorful Displays and Scent Communication

Social Structure

With their brightly hued muzzles and Rear ends, mandrills are aptly dubbed “the clowns” of the African rainforests they inhabit in Cameroon, Gabon, Congo and Equatorial Guinea. But that flamboyant painterly display advertising males’ maturity, health and social rank serves a serious purpose.

Within large and fluid groups up to 800 mandrills led by dominant alpha males, these visual cues help diffuse tensions and reinforce hierarchies as noisy hordes forage the jungle for fruit, seeds and insects or cluster at night in trees. Females also sport reddish noses and rumps which may signal fertility cycles to potential mates. Intriguingly, mandrills possess sternal glands too – scent organs researchers believe may add an olfactory element that humans can’t perceive.

Environmental Pressures

Despite adaptations enabling peaceful group coexistence bounded by clear comunication avenues, mandrill populations have plunged over 50 percent in the past 30 years. Deforestation for oil palm and pulp wood cultivation removes feeding grounds and refuge sites, while bush meat hunters target all ages with snares that lead to infection and potential hand amputation.

The Wildlife Conservation Society now classifies them as vulnerable to extinction, making research on behavior and implementation of protected area policies urgent priorities.

Preservation Outlook

Supported by eco-tour programs that fund habitat patrols, researchers suggest better transboundary planning to preserve corridor links between national parks and reserves. Community mandrill guardian initiatives also help foster cultural attitudes that take pride in these colorful primates rather than see them as meat or pet trade commodities.

While still in need of wider habitat coverage, such integrated efforts give hope that the mandrill’s flamboyant nose displays will continue to animate African forests for years to come.

9. The Long-Nosed Bandicoot: An Australian Forager

Foraging Adaptations

From scrublands to grassy woodlands across Australia’s northern and eastern coasts roams the long-nosed bandicoot – a rabbit-sized marsupial endowed with a tapered, 7-inch nose ideal for rooting out insects, larvae and fungi.

Their elongated snouts and claws are perfect tools for digging holes in search of centipedes, spiders and subterranean plant morsels to devour. While foraging under the cover of darkness given their largely nocturnal nature, bandicoots also use their nose bones, called rostral gyri, to detect prey through subtle air pressure changes. This unique system guides precise strikes.

Ecosystem Contributions

All that scurrying and digging by long-nosed bandicoots contributes to soil health and biodiversity by continually turning and aerating earth, incorporating organic matter, and dispersing seeds or spores via their scat. Studies show bandicoot activity areas host more diverse vegetation than unused plots.

Yet due to predation and habitat loss from agriculture, invasive species and sprawling development, bandicoots have disappeared from nearly 40 percent of their former range, concentrating more in eastern Australia but declining across that breadth too in spots.

Conservation Status

Listed as near threatened, local groups now nominate the long-nosed bandicoot as vulnerable in states like New South Wales and South Australia given population crashes and increased predation pressures. Wildlife agencies urge protecting remaining shrubland corridors and regeneration sites, clearing foxes and cats from refuge zones, and raising public awareness on giving native diggers safe roaming room.

While shy and seldom seen, the loss of this unassuming ecological gardener ripples across entire landscapes it once spontaneously cultivated.

10. Snub-Nosed Monkeys: High-Altitude Specialists

Anatomical Adaptations

Occupying China’s remote mountain forests up to 4,700 meters are Asia’s only temperate primates – the snub-nosed monkeys, so dubbed for their shortened muzzles and nostrils. Of five Rhinopithecus species, the black and gold and Guizhou snub-nosed monkeys are most imperiled at fewer than 750 individuals each.

These graceful primates huddle in closely knit bands up to 800 strong for warmth and protection, using their specialized wide, flat noses to inhale larger volumes of crisp air with minimal moisture loss. Dense fur layered upon grizzled, oil-secreting skin locks in heat too, while long, muscular tails act as blankets when wrapped around their bodies.

Dietary Resources

Feeding almost exclusively on leaves, lichen, pine needles and bark, these high-altitude leaf-eaters fill a dietary niche enabling survival despite harsh winters. Loose social networks facilitate information exchange on best feeding sites across seasons. Their unusual adaptations also make them a source of fascination for primatologists studying the environmental pressures driving evolutionary variation.

Sadly, economic development like mining, logging and road-building increasingly encroach on the isolated highland pockets harbouring these endemic monkeys found nowhere else on Earth.

Conservation Outlook

Listed as endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), just 2,500 snub-nosed monkeys remain across fragmented habitat and small, struggling groups facing inbreeding risks long-term. Bolstering protections for China’s national reserves while expanding mixed-use buffering corridors offers the best hopes for preserving viable populations.

Groups like the Nature Conservancy also promote ecotourism initiatives funding park patrols against poaching to change local attitudes towards seeing snub-nosed neighbours as assets. There is still time to ensure the monkey’s cozy round noses can warm in peace again.

Conclusion: The Remarkable Adaptations of Big-Nosed Animals

As we’ve explored, nature has crafted truly astonishing nasal adaptations enabling unique lifestyles and ecosystem balances across habitats – from star-nosed moles to sawfish. While some facial structures aid sensory capabilities, social dynamics or respiration, all represent evolutionary ingenuity. Sadly, many big-nosed species now face grave risks from human activity.

Preserving precious wilderness spaces and supporting the work of conservation groups fighting threats like poaching and habitat loss represents our best chance at protecting these marvels of natural selection.

We encourage readers to learn more about wildlife conservation efforts and contribute however possible, whether through political advocacy, donations, ecotourism or everyday choices supporting sustainable resources. The magnificence of the natural world relies on such combined commitments.

- What Should I Do If A Koala Bites Me? Safety Guide - 2024-05-30

- Are Kangaroos Born Without Hind Legs? A Fascinating Journey - 2024-05-30

- Animals That Look Like Squirrels - 2024-05-30